The Fed’s response to COVID will zombify corporate America for a generation

Written June 21, 2020

In “The L-Shaped Recovery“, we predicted that a combination of demand destruction, job market uncertainty, rising debt, and a shift in consumer behavior would hinder the economy from achieving a rapid recovery from the COVID pandemic.

Since that writing, the Fed has taken the unprecedented step of intervening directly in support of the credit markets, producing a spectacular V-shaped rebound in the financial markets. But as we all know, the market is not the economy.

The economic template that the current public health crisis is most often compared to is the Great Depression of the 1930s, but a more instructive precedent for what the future holds might be that of Japan, which is still trying to shake off the effects of the financial market bubble that popped in 1989.

To put the excesses of 1980s Japan in context, it was said that the 280 acres of land within the walls of the Imperial Palace in central Tokyo was worth more than the entire state of California. At the time, this became the benchmark against which all other insane real estate and lending valuations were linked. When it inevitably crashed, Japan, Inc. tried borrowing their way out of trouble. More than 30 years later, and after racking up an eye-watering debt-to-GDP ratio of 279%, they’re still trying to find a way out.

In Japan, bankruptcy is not seen as a financial tool deployed to clear the decks of bad debt but rather as a cultural stain, one of humiliation and loss of face. So corporate Japan, and the country itself, stumbles onward like a zombie, burdened by mountains of legacy debt, unable to reap the benefits of innovation that leaner balance sheets would enable. This interminable trap is so ubiquitous that it even has its own name: Japanification.

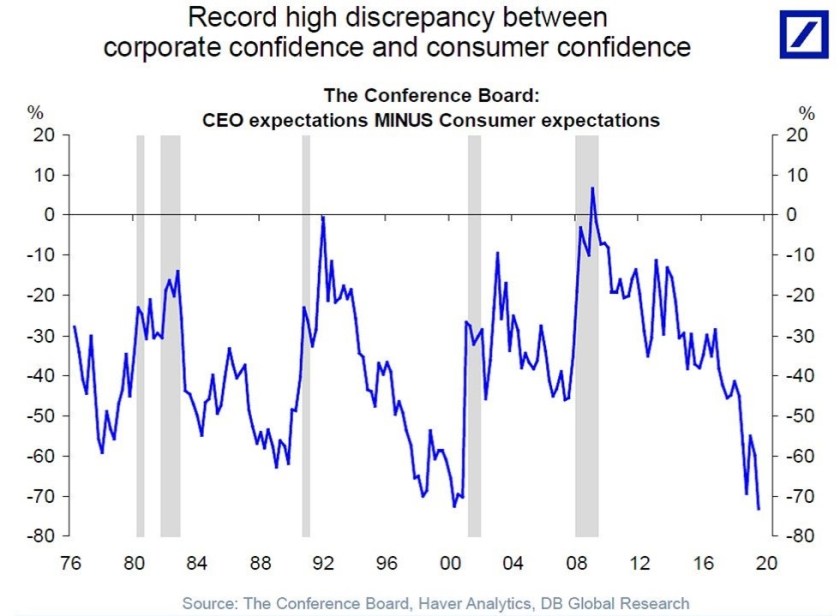

Unfortunately, the Fed is headed down a similar path. Not only by backstopping the credit markets but by actively pushing prices higher, the Fed has allowed almost every corporation access to cheap money. It may be necessary, but just like the never-ending policy of quantitative easing destroyed the price discovery function in the equity markets, the unintended consequence of credit intervention is doing the same to the bond market. Normally where good corporate governance is rewarded and bad decisions are punished, everybody now gets a trophy.

In my day job as an editor for a financial news service, I spend a large portion of my time reading press releases from companies tapping into an almost unlimited supply of liquidity in the credit markets, with most of it going to refinance revolving bank debt incurred during the pandemic. Borrowing is literally exploding.

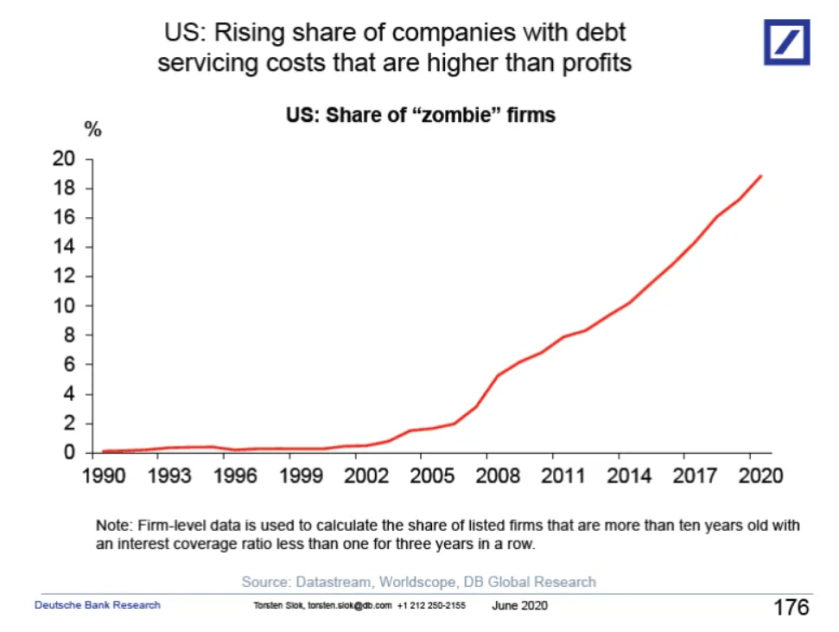

While this widespread refi effort is tactically beneficial in the near term to bridge the gap in cash flow created by the virus lockdown, the long term risk is that it will allow bad capacity to remain on the books, keeping unproductive companies alive and leaving little room for innovation and for fresh entities to thrive.

Corporate America was already running record levels of debt and leverage before the pandemic hit. Half of the investment-grade bond market is precariously rated BBB, just one notch above junk. Wide-scale bankruptcies and credit downgrades are indeed a systemic threat in a weakened economy, and it is forcing the Fed’s hand to prevent the entire system from snowballing downhill and out of control. But, like Japan, the unintended consequence of today’s policies will be a debt burden that will take years, if not decades, to climb out from under.

In a note to clients last week, Bridgewater Associates’ Ray Dalio warned of a “lost decade” for the equity markets as profit margins get squeezed by debt servicing costs. See here https://bloom.bg/3hMBVtC.

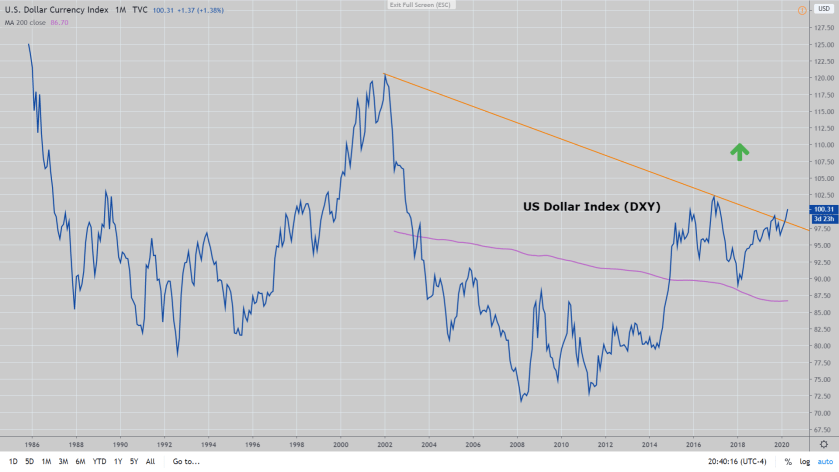

We tend to agree and would use this recent rebound in financial markets to reduce risk exposure while sticking with core long positions in the US dollar, short-term treasuries, and gold.