Despite a quick reopening, a crack in the Chinese currency suggests things are about to get worse for the world’s second-largest economy.

Written May 24, 2020

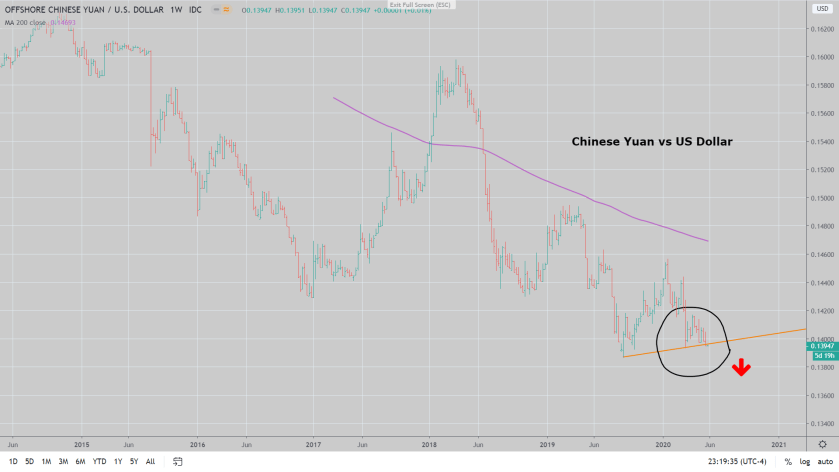

The Chinese yuan finished last week near its lowest level in more than a decade as investors began to bet with their feet, heading for the exits over concern that the country is compounding its economic problems with geopolitical moves that are already generating widespread condemnation and even greater uncertainty.

The post-pandemic economic landscape presents a test for the regime that has long prided itself in delivering on an unspoken bargain where one-party rule is tolerated in exchange for consistent economic growth.

However, a sure tell that the government’s grip is slipping was its failure to set an economic growth target for the upcoming year during last week’s National People’s Congress, the annual planning meeting of the Chinese Communist Party. It might seem like an insignificant detail, but for the first time since it began providing GDP estimates in 1990 the central body declined to be bound by a projection that it may not be able to meet. It is a big deal, and the obvious conclusion is that the economy on the mainland is worse than it outwardly appears.

China’s recalcitrance in dealing with COVID-19 has also turned global public opinion against it. As a result, doing business with the Chinese in the future is going to come under much more scrutiny than in the past.

Despite the allure of 1.4 billion potential consumers, it now won’t be so easy to turn a blind eye to the tilted playing field China has erected to their advantage, as much of the world has done since China’s inclusion into the World Trade Organization in 2001.

The U.S. Senate took the first step last week by passing a bill by a 100-0 margin requiring Chinese firms to adhere to American accounting standards or risk being delisted from our exchanges, also a big deal. Other measures will follow.

The pandemic exposed many countries’ over-reliance on Chinese manufacturing and is forcing most to reconsider basing their supply chains elsewhere. Japan even earmarked part of its economic stimulus fund specifically to help its manufacturers shift production out of China.

The bottom line is, the rules of international trade are being rewritten and China is not going to like the changes.

Further complicating matters, China is lashing out at the west’s insistence on an investigation into the origins and handling of the virus. Within the space of a few weeks they’ve made moves to block certain Australian exports, threatened to cut off the supply of critical pharmaceutical ingredients to the U.S., and imposed their own national security laws on Hong Kong. So much for the idea of “one country, two systems” that was the founding principle agreed to by both parties when the British turned Hong Kong over to China in 1997 and that has allowed the former colony to thrive as an international financial center.

Not content to stop there, the Chinese navy is scheduled to begin live-fire military exercises later this month as part of an amphibious assault training operation on an island controlled by Taiwan. As the Wall St. Journal asked in a May 21 op-ed titled “China Moves on Hong Kong”, is Taiwan next?

At the risk of stating the obvious, political isolation from global trading partners can only be seen as a negative for the economy.

Plan A for Chinese authorities to counteract these economic headwinds is with traditional fiscal and monetary stimulus, along with a heavy dose of infrastructure spending. But the effectiveness of that approach is questionable as the country is already swimming in overcapacity, and debt. It’s the demand side of the equation that is lacking.

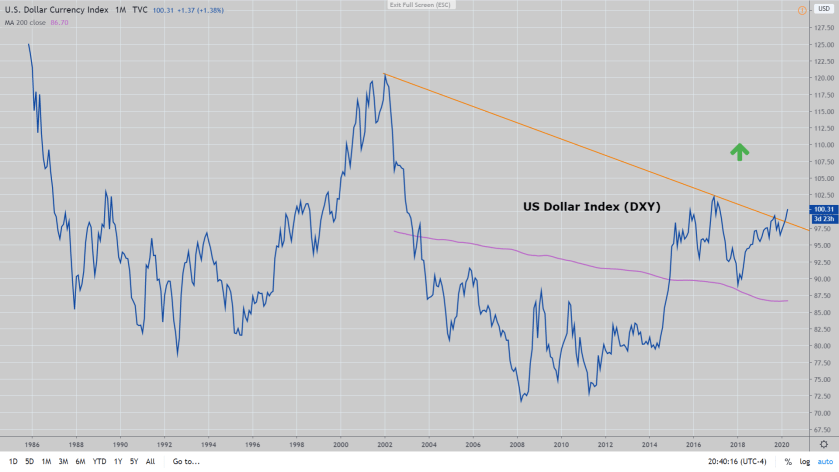

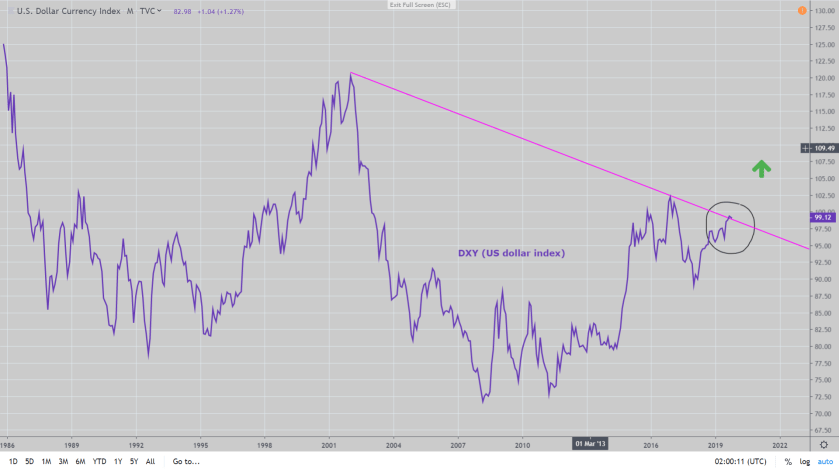

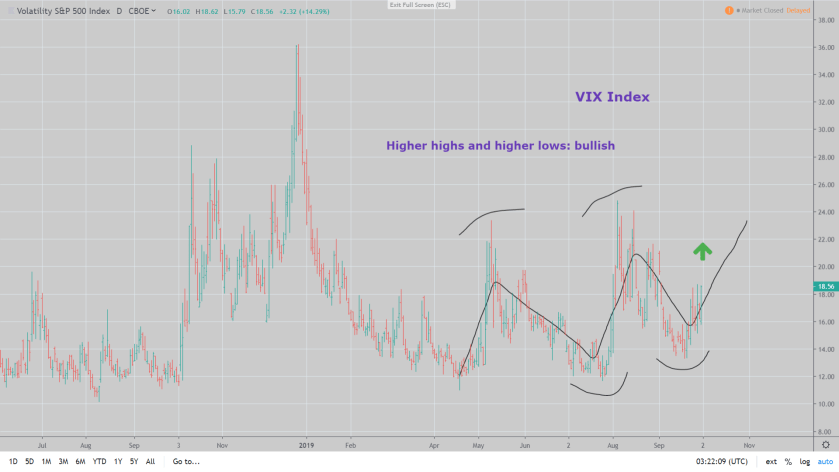

Plan B would be a devaluation of the currency, which the market is beginning to sniff out. In theory, this would spur demand by making Chinese-produced goods more competitively priced. In reality, it would propel the dollar higher, unleashing a deflationary wave on a world already under enormous pressure from falling prices.

The Fed and other central banks have done an impressive job of rescuing the credit and equity markets from the depths of the pandemic panic in March, but a Chinese devaluation would slam the lid on any hopes of reflating the global economy.

Our core portfolio positions remain long of the US dollar, front-end treasuries, and gold.